The FT Moral Money Forum is supported by

Foreword

Simon Mundy, Moral Money Editor, Financial Times

It is exactly 35 years since the extraordinary takeover battle for tobacco group RJR Nabisco — later immortalised in the book Barbarians at the Gate — which proved a landmark in the leveraged buyout boom of the 1980s.

Henry Kravis and Stephen Schwarzman are now elder statesmen of the US financial sector, and the term “LBO” has fallen out of use, replaced by the far more stately-sounding “private equity”.

Yet this industry has not quite managed to shed its reputation as a swashbuckling, money-hungry sector that can leave chaos in its wake. That is a problem in a time when investors — including the institutional clients and wealthy individuals that private equity firms rely on for funding — are starting to pay real attention to environmental, social and governance matters.

In the newest of her series of deeply researched Moral Money Forum reports, Sarah Murray digs into the work that private equity firms are doing to equip themselves for the ESG era, and the lively debate over their place in it.

Some argue that they are uniquely well-placed to push their portfolio companies to move rapidly on sustainability, and to pursue long-term (or at least medium-term) value creation without the distraction of quarterly earnings reports and daily share price fluctuations. Critics contend that the sector’s pedigree of “asset-stripping”, sometimes with dire impacts on workers, makes it impossible to take its ESG claims seriously.

Whatever your view, the debate over the role of this giant industry is vital to understand, as this excellent report makes plain.

Can private equity meet public responsibilities?

The sums of capital the sector wields could be critical to financing a sustainable economy, but greater transparency and accountability are needed to ensure this happens.

by Sarah Murray

To say that opinions on private equity’s sustainability record are divided would be a wild understatement. When we polled FT Moral Money readers, respondents offered everything from the view that private equity has “always done ‘ESG’ because it is simply good investing” to a characterisation of firms as “parasites on the living body of democratic capitalism”.

As the latter comment indicates, the sector has, to put it mildly, something of a reputational challenge. With a typical annual management fee of 2 per cent of managed funds – plus 20 per cent of investment gains – the private equity moneymaking model has created an army of billionaires.

But detractors blame firms for sins from running nursing homes into the ground to snapping up the dirty assets of oil and gas majors as they divest from fossil fuels. Others worry that the industry’s vast portfolios of companies give it an unhealthy hold over society and the economy.

Private equity certainly wields economic clout. The sector has trillions of dollars invested in industries from real estate and healthcare to energy and manufacturing. In the US, companies owned by private equity made up about 6.5 per cent of gross domestic product in 2022, according to the American Investment Council, a private equity lobby group.

However, some argue that its longer-term approach and model of value creation based on growth capital – supporting the expansion of companies that have outgrown venture capital funding – makes the sector what Saïd Business School professor Robert Eccles has called a “transformation engine” for progress towards a more sustainable economy.

While this engine has taken time to shift gears, large private equity firms are now working hard to position themselves as sustainability leaders.

This is partly a response to the demands of their limited partners – the hedge funds, pension funds and other institutional investors on which they rely for funding.

Some are seeing opportunities, too. “The lesson we’ve learned from the past 15 years is that an approach to ESG and sustainability that is focused on issues material to a company’s bottom line can be incredibly accretive from a value creation and value protection perspective,” says Ken Mehlman, co-head of the global impact fund at KKR, which launched its “green portfolio program” in 2008.

Sustainability strategies can also serve to manage risk. “There’s a recognition that the need to address things like climate change is inescapable,” says Michael Moore, chief executive of the BVCA, the UK private equity industry association. “The evidence is there in front of people’s eyes.”

For outsiders, the industry’s opaque nature prompts questions about the seriousness of firms’ pledges on sustainable business practices. “It’s hard to know exactly what private equity is doing with their companies because by default they’re private,” says Bruce Usher, a Columbia Business School professor and author of Investing in the Era of Climate Change.

However, he argues that the sector’s pragmatic approach comes with advantages. “Private equity is very focused on increasing the efficiency and profitability of businesses,” he says. “If you can align that with things like reduced energy use, that’s not greenwashing.”

So, decades on from the heady days of 1980s leveraged buyouts, has the leopard really changed its spots? And what could bring to private capital the transparency and accountability needed to ensure it is genuinely contributing to a more sustainable economy?

Harnessing the value-creation model

When asked to identify the biggest driver of private equity firms’ increased interest in ESG strategies, most FT Moral Money readers pointed to the potential for competitive advantage.

Moore agrees that this is a crucial motivation for BVCA members. “They can all see that finding solutions to climate change or helping the economy adapt to decarbonisation is a hugely significant area of opportunity,” he says.

Private money is certainly flowing into one sector that is essential to the transition to a low-carbon economy. In 2022, private equity investment in renewable energy and cleantech in the US alone stood at more than $26bn, up from about $16bn in 2021, according to the AIC.

The climate crisis is also prompting firms to make new kinds of investments, such as Blackstone’s 2021 acquisition for $1.4bn of data management company Sphera, which helps clients identify and mitigate ESG risk.

Nor is the climate the only area of focus. Diversity and social equity are rising up the agenda. KKR, for example, has a programme through which it supports its portfolio companies in introducing employee engagement measures such as giving staff shares in addition to salaries, which increases retention, improves productivity and enhances profitability.

Meanwhile, a structural shift in the industry has given it greater incentive to take sustainability seriously. In the days when firms were known primarily as buyout kings, they were able to reap the benefits of efficiency gains through internal restructuring.

“A lot of that low-hanging fruit has been picked,” says Eccles, who chairs KKR’s Sustainability Expert Advisory Council. Today, growth capital is the dominant model, which he says needs to go beyond efficiency to address everything from climate change to workplace diversity. “These are things we weren’t thinking about in the 60s and 70s.”

The growth capital model supports much of this. Because they take large stakes in the companies in their portfolios, firms can use board representation and ongoing dialogue with management to push companies to implement more ambitious sustainability strategies.

“You don’t need to worry about shareholder resolutions – you just call the chief executive,” says Andrew Howell, senior director of sustainable finance at US advocacy group Environmental Defense Fund. “That puts GPs [general partners] in a great position to drive real implementation of what needs to be done for the transition.”

Given that their portfolios consist of companies that are generally smaller than their listed counterparts, GPs – that is, the firms that manage private equity funds – also have more room for manoeuvre than public markets investors. And because they are not subject to quarterly earnings reporting, they can set their own agendas.

“When you measure success over years as opposed to quarter to quarter, you’re more likely to achieve your objectives,” says Mehlman.

Jamal Hagler, the AIC’s vice-president of research, cites investments in new energy or energy transition infrastructure. “Technologies that have upfront costs, but long-term returns, can be a bit more difficult to do in the public markets,” he says. “Certain things need to be outside the public-market glare to scale up and grow.”

GPs can also offer the companies in their portfolio access to knowledge and expertise built up through their investments. “They can bring resources to bear that a small to medium-sized company might not have alone,” says Sarah Keohane Williamson, chief executive of FCLTGlobal, a Boston think-tank that champions long-term investing.

One example of this is at EQT. The Swedish private equity group is helping all the companies in its portfolio to set science-based targets (which align with efforts to keep global warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels) and to have them validated through the Science Based Targets initiative.

“As we scale this across the portfolio, we bring learnings from the first round to the second round,” says Bahare Haghshenas, EQT’s global head of sustainable transformation. “Scalability when it comes to sustainability is an important part of the private equity model.”

For companies struggling to integrate sustainability into their operations, the combination of growth capital and expertise can be appealing. Moral Money survey respondents who identified their organisation as a private equity portfolio company cited support from their management teams as the most important factor in shaping their sustainability strategies.

“If you’re a small company, life is hard enough as it is, with all the changing expectations and regulations,” says Eccles. “For a portfolio company, what’s not to like?”

With investments in thousands of companies, larger firms have an opportunity to scale up their sustainability strategies by transferring technology and knowhow across the portfolio. “That’s why there’s some hope that they can be a positive force,” says Williamson.

In the private equity industry, approaches to sustainability tend to involve implementing net zero, diversity or other strategies in the operations of companies. However, in another model, investments are directed into groups or start-ups with social impact as their core purpose. This was the objective of private equity firm TPG in creating the Rise Fund, which it launched in 2016 with its first fund which raised $2.1bn.

At the time, impact investing was largely taking place through venture capital, but in relatively small investments. “That was not sufficient to make the change we needed to make in the world,” says Maya Chorengel, co-managing partner. “To scale, we had to grow the industry beyond venture capital and into growth equity and later-stage capital.”

While the company’s main focus is reducing emissions in its operations, many of its activities are hard to decarbonise.

Using the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals as an investment guide, the fund invests in companies that provide everything from renewable energy to digital education, global disease intelligence, plant-based food and low-cost healthcare. “We chose sectors that TPG has familiarity with,” Chorengel explains. “And we used the SDGs as the north star for identifying the outcomes we wanted to achieve.”

The goal was also to ensure that impact was measured as rigorously as financial returns and that the effect of the fund’s portfolio companies was “additional” – that is, over and above the impact that would happen without the company.

This led TPG to develop Y Analytics, which uses data, evidence and third-party research in its impact assessments. Using the Y Analytics methodology, the Rise Fund estimates that by 2022 it had generated positive outcomes worth almost $9bn across its funds since its inception.

“For any at-scale impact venture, we don’t have time or capital to waste,” says Maryanne Hancock, Y Analytics chief executive. “So when the fund was created, the challenge was to be as effective as possible with the dollars we had.”

Good, bad or ugly?

To some the idea that firms traditionally known for a “buy, strip and flip” model of capitalism are claiming to lead on sustainability is laughable. Detractors include Elizabeth Warren, the Democratic senator from Massachusetts, who has been unequivocal in her characterisation of the sector.

“Private equity firms get rich off of stripping assets from companies, loading them up with a bunch of debt, and then leaving workers, consumers, and whole communities in the dust,” she said in 2021 on reintroducing legislation that would, among other things, make it harder for firms to load companies with debt to finance acquisitions. The bill’s title says it all: the Stop Wall Street Looting Act.

Scrutiny of private equity is intensifying further as antitrust regulators home in on the anti-competitive behaviour of a sector that now owns large chunks of the economy.

Some regulators have pointed to the negative social effects of this ownership. In a 2022 interview with the Financial Times, US Federal Trade Commission chair Lina Khan talked of the “life and death consequences” of private equity acquisitions, citing research showing an increase in mortality rates after nursing homes were purchased by these firms.

Another concern is that as big energy companies work to clean up their carbon footprint by selling off their dirtiest assets, these assets are ending up in the hands of owners backed by private equity that can be subject to less scrutiny when it comes to their environmental commitments.

There is no shortage of negative data on private equity as watchdogs seek to check the sector’s climate credentials.

The Private Equity Stakeholder Project, an advocacy group, produces regular reports on the social and environmental impact of private equity firms. In September, for example, it highlighted the expansion of investments into fossil fuels by KKR, including three liquefied natural gas projects, two of which it says have been cited for environmental violations.

“Private equity is quietly buying up pretty extensive conventional energy assets, as well as expanding them, and there’s no accounting for it,” says Alyssa Giachino, PESP’s climate director.

Another organisation keeping tabs on private equity’s footprint is the Anthropocene Fixed Income Institute, a climate-focused non-profit founded by former bond portfolio manager Ulf Erlandsson. He argues that because of the lack of consistent climate and nature reporting at the manager and portfolio company level, investors may unwittingly be putting their money into funds containing assets that run contrary to their ESG commitments.

Of course, whether or not you think private equity ownership of fossil fuel assets is a bad thing comes down to which side you take in a familiar argument: whether engagement or divestment is the best way to clean up dirty companies.

At Carlyle, Megan Starr, the firm’s global head of impact, argues that owning and decarbonising these assets is a more effective strategy. The firm has been acquiring traditional energy assets, such as Spain’s Cepsa, one of Europe’s largest oil and gas companies, with which it has developed an energy transition plan that includes a focus on sustainable mobility, biofuels and green hydrogen produced from renewable sources.

“The largest decarbonisation potential is in the most carbon-intensive businesses,” says Starr. “If we don’t invest in those businesses, our portfolio looks ‘clean’ on paper but that doesn’t change the amount of carbon in the atmosphere.”

Other firms have made similar arguments. However, if the private equity sector is to convince the rest of the world of the merits of this strategy, increased transparency will be critical.

“One of the issues with private equity structuring is it’s opaque so it’s harder to monitor,” says Erlandsson. “An investor should be able to understand the climate impact of the manager and of each asset, but the private sphere tends to cherry-pick the data it shares.”

Another side to the profit coin

If some see industry profit motives as part of the problem, Eccles takes a contrasting view. He argues that the profit motive may help to provide assurance that firms are genuinely committed to sustainability.

Private equity firms, he says, are only likely to invest in implementing sustainability strategies across their portfolios if they believe they will bolster long-term profitability. “There would be no reason for big firms to pay attention to sustainability if it wasn’t linked to value creation,” he says. “Because that’s how they get paid.”

As a relative newcomer to the sector, Haghshenas (who before joining EQT was a Deloitte partner) sees the potential to strengthen this link and help portfolio companies move away from treating sustainability as primarily a matter of reporting and compliance. “Connecting sustainability to performance and value creation is how we see this coming to life,” she says. “That’s definitely the opportunity we have ahead of us.”

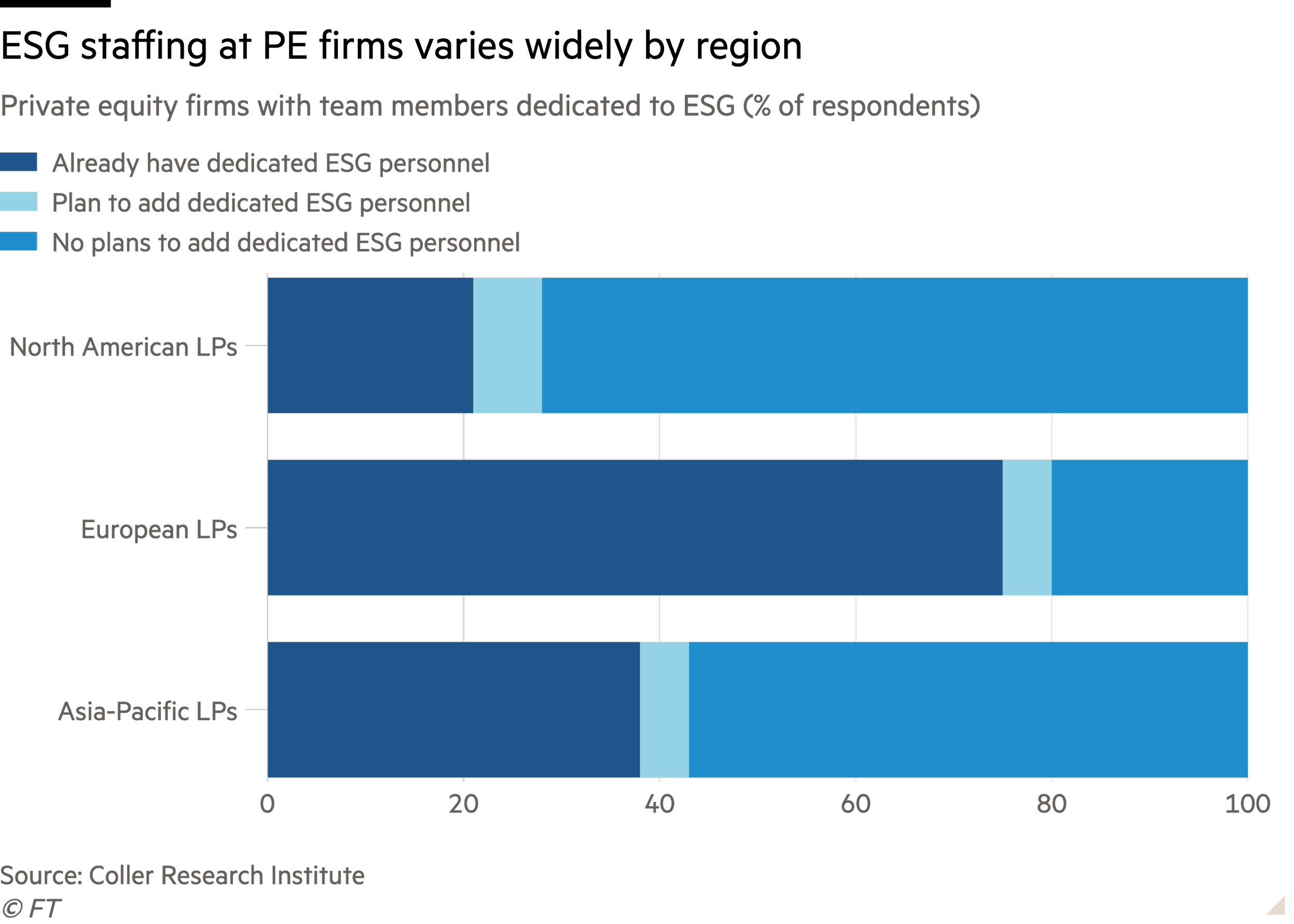

In addition, private equity firms are being nudged towards sustainability strategies by another force: their investors. To meet their own sustainability mandates, LPs are pushing the GPs they invest in to work towards everything from carbon reduction to employee diversity.

In a 2023 Edelman Smithfield survey, 30 per cent of LPs said that ESG was more important than investment returns when it came to allocating funds to private equity firms, while 60 per cent wanted to understand a firm’s ESG-linked financial incentives before deciding to invest.

FT Moral Money readers have noted this trend. When asked to identify the most powerful driver behind private equity’s embrace of ESG strategies, the second-largest group (after those citing desire to reap competitive advantages) pointed to pressure from investors.

Claudia Zeisberger, professor of entrepreneurship at Insead, goes further. “Right now, there’s not a private equity fund out there that can raise money without having something to say about environmental and social issues and governance,” says Zeisberger, who also founded the business school’s Global Private Equity Initiative. “It’s the LPs that call the shots, and for all of them this has become an important part of how they deploy their funding.”

Increasing the pressure for GPs is the fact that the days when investors were lining up to get in on the private equity act are over – for the moment, at least. “A lot of private equity firms are trying to raise money and having a harder time doing so,” says FCLTGlobal’s Williamson. “So the LPs have more leverage today than they’ve often had.”

Questions over questionnaires

One of the things LPs are looking for is better disclosure on ESG performance. And many have stepped up their due diligence on sustainability, according to BVCA’s Moore. “It’s off the scale,” he says. “The questionnaires have huge sections on ESG. They benchmark the investments and look for data to feed back to pension schemes and other LPs.”

This does not mean the sector’s ESG measurement and disclosure questions have been resolved – far from it. In fact, if there is one thing that everyone from activists to LPs and GPs can agree on it is that better data is a priority.

FT Moral Money readers ranked transparency second (after greater regulation) among measures that would enhance private equity’s ability to contribute to a sustainable economy. Yet when we asked GP respondents how they track progress on the sustainability of the companies in their portfolio companies, their answers revealed the sector’s biggest data challenge: lack of consistency.

FT Moral Money readers said they used methods ranging from annual questionnaires and discussions at board meetings to continuous assessment, regular monitoring and reporting, hiring of outside advisers, collaboration with deal teams, internal operations teams and ESG teams – and a mixture of all of the above.

At PESP, Giachino says that similarly heterogeneous approaches prevail in the data GPs supply to their investors. “Because there’s no standardised disclosure, each firm tells the story it wants to tell.” She says PESP has developed an investor questionnaire on areas such as fossil fuel risk exposures, energy transition strategies and climate lobbying.

As ever, however, the debate over whether ESG data should be one-size-fits-all, or specific to companies and sectors, divides opinion. “It may be easier for GPs to work directly with the LPs for the information they need,” says AIC’s Hagler. “Broad data sets don’t necessarily satisfy that need.”

He argues that the sustainability factors material to, say, an oil and gas company and a software-as-a-service business may be very different. “We want to make sure there’s enough flexibility so that GPs and LPs can access the information that’s best for them.”

Debates over specific versus generalised data will no doubt continue. But one thing seems clear: varying approaches to private equity data are creating increasingly heavy workloads.

Suzanne Lupton, director of co-investment at Maven Capital Partners, says that “disparate and competing reporting standards across the industry” can make information gathering and reporting “more onerous than it might otherwise be”.

Starr agrees. “We’re getting north of 300 ESG data requests at Carlyle every year and they’re all in slightly different formats with slightly different definitions,” she says.

In 2021, with volumes of bespoke data requests rising, a group of private equity firms and investors led by Carlyle and Calpers, the Californian pension fund, launched the ESG Data Convergence Initiative.

The aim is to provide consistency in measurement and reporting of sustainability performance in the private equity sector. “We needed to converge on a smaller set of data points so we could see what was happening,” says Starr.

In October of the same year, investors including the Ford Foundation, S&P Global, private markets adviser Hamilton Lane and Omidyar Network launched Novata, a US-based public benefit corporation whose platform is designed to make it easier for private markets to collect, analyse and report on sustainability data.

Part of the impetus behind the creation of Novata was to bring private market disclosure in line with developments on measurement and disclosure that have taken place in public markets in recent years.

“You couldn’t have ever more stringent requirements in public markets and not expect investors with diversified asset allocation across public and private markets to ask similar questions on the private market side,” says Margot Brandenburg, Ford Foundation’s senior programme officer for mission investments.

More broadly, she sees data as critical if the sector is to play a bigger role in the transition to a sustainable economy. “The potential is there for private equity companies to punch above their weight on sustainable development issues that are important for everyone on the planet,” Brandenburg says. “But there needs to be real data, infrastructure and intention for that to play out.”

Some use existing tools and standards that have been developed for public markets, such as SASB, which is also applicable to private equity portfolios when it comes to assessing social and environmental issues that are material to value creation. “Using those third-party frameworks and advisers is important,” says KKR’s Mehlman. “That helps us be smarter.”

Out of the shadows

While transparency within the sector is improving, it is available largely to industry insiders. As the proliferation of critical media stories and damning reports from advocacy groups suggests, this frustrates those looking in on the sector from outside.

“Money drives everything,” says Hugh Brown, global head of financial services at BSR, a corporate social responsibility advisory group. “So for those that invest, there’s going to be relative transparency available. For outsiders, that level of transparency is going to be difficult to obtain.”

Mehlman argues that it is important to talk to detractors. “We’ve always had an open door to people who are sincerely interested in engaging,” he says, citing former union leader Andrew Stern, an erstwhile fierce critic of KKR who is now a member of the firm’s Sustainability Expert Advisory Council.

Brandenburg believes accountability needs to extend beyond the walls of the sector. “It’s a large and growing slice of the global capital markets so it’s relevant no matter what,” she says. “But it’s also relatively opaque and ill understood by stakeholders who should know, because their lives are being impacted.”

Given the sums of capital it can wield, private equity could be critical to financing everything from clean energy infrastructure to workforce development. And with plenty of tools at their disposal, firms are setting ambitious goals for strategies that, if realised, could contribute to a cleaner, more equitable economy.

Yet it is struggling to shake off its image as a rapacious sector with a slash-and-burn business model. If private equity is to be credited for meeting its sustainability objectives, it may need to set one more goal: to bring itself out from the shadows.